GAINESWOOd

Site History

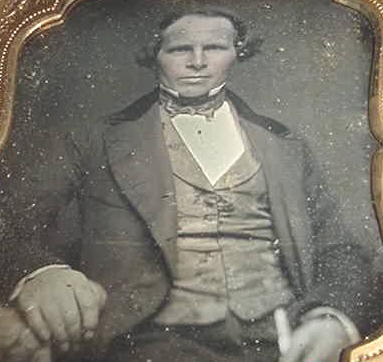

The history of the Gaineswood site and mansion, archaeological site 1MO56, is linked mainly to two individuals-George Strother Gaines and Nathan Bryan Whitfield.

It is believed that, prior to 1800, Marengo County (including Demopolis) was a hunting ground for native Americans. Archaeological studies have not yielded physical evidence of prehistoric occupation at Gaineswood. However, its location on a high ridge toe 160 feet above sea level would have made it a favorable location for a campsite or dwelling.

The site’s topography and proximity to two rivers (Tombigbee and Black Warrior) likely influenced George Strother Gaines’s decision in 1819 to purchase from the U.S. government 480 acres encompassing the site.

Gaines was

destined to play a huge role not only in the history of the Gaineswood

site, but also that of Demopolis, the state of Alabama, and the 1830 Choctaw

removal. It was Gaines who encouraged incoming French exiles in 1817 to

establish their Vine and Olive Colony at what soon became Demopolis, “the

people’s city.” In 1819, the same year he bought his 480-acre estate now

engulfed by the city of Demopolis, he served as a commissioner on the city’s

first governing body. In 1825 he served Marengo County as a state senator. In

1821, Gaines built “comfortable cabins” where on site where Gaineswood was later

built, and he lived there until 1831. According to Whitfield family records, a

dogtrot cabin in which Gaines lived became the nucleus for Nathan Bryan

Whitfield’s 1843-1861 evolution of his extraordinary Greek Revival mansion.

By 1832, Gaines had moved himself and his family to Mobile. Yet he did not immediately sell his Demopolis estate, perhaps holding it as an investment. He left the care of the estate in the hands of his nephew, attorney Francis Strother Lyon, who became in 1832 the owner of Bluff Hall and eventually an important political figure in Alabama. In 1842, Gaines authorized Lyon to sell the estate to Nathan Bryan Whitfield.

A cotton planter and Renaissance man of his time, Whitfield had emigrated from North Carolina to Marengo County in 1834. Having received reports of inexpensive, yet fertile soils for growing cotton, Whitfield and many other Carolina planters were attracted by the economic and agricultural potential of “The Canebrake” (later called the Black Belt).

Whitfield, his wife Betsy, and children first lived in an “open cabbin” on his large plantation near modern-day Jefferson, in western Marengo County. By 1837, Whitfield had accumulated a flourishing cotton plantation of 4,000 acres, part of which bordered the Tombigbee River, thus making it easy to load his crop onto flatboats bound for the seaport of Mobile.

But a devastating epidemic in 1842, which claimed the lives of three children within a six-week span, forced Whitfield to consider moving his family to a new and healthier home.

Whitfield decided to buy Gaines’ 480-acre estate near

Demopolis for $5,000. By 1860 the estate has grown to

1600 acres.

Whitfield finally had the great opportunity to build his dream

home. It is unknown what his concept of “dream home” was in 1843, but it is

well documented that Whitfield continuously refined his concept throughout the

18-year construction period.

Whitfield finally had the great opportunity to build his dream

home. It is unknown what his concept of “dream home” was in 1843, but it is

well documented that Whitfield continuously refined his concept throughout the

18-year construction period.

With the help of artists, craftsmen, and other talented persons, including African-American slaves, Whitfield enlarged and refined the home to his liking. By 1856 he had decided to name his mansion Gaineswood in honor of George Strother Gaines. By 1860 he had added domed ceilings (link) with window lanterns to the parlor and dining room.

Also by 1860, the exterior and folly landscape were completed to the point that Whitfield

hired artist John Sartain to produce a detailed steel engraving of the home’s

façade and grounds. The signature features of the landscape (above) were the

hand-dug artifical lake fed by an artesian well and the circular summerhouse

pavilion fronting it.

were completed to the point that Whitfield

hired artist John Sartain to produce a detailed steel engraving of the home’s

façade and grounds. The signature features of the landscape (above) were the

hand-dug artifical lake fed by an artesian well and the circular summerhouse

pavilion fronting it.

Whitfield’s plans for more refinements were interrupted by the Civil War. After the war, complications from a leg injury sustained in an 1862 fall resulted in his death in 1868.

Institutional History

Whitfield’s heirs retained ownership of Gaineswood mansion until 1923, when the home was sold to Mr. and Mrs. Clarence Kirven. In 1945, the Kirvens sold the home to Dr. and Mrs. J.D. McLeod. In 1966, the State of Alabama bought Gaineswood from the McLeods for $92,775, and from 1971-1975 the Alabama Historical Commission (AHC) led a $500,000 restoration of Gaineswood to its 1860 appearance. On November 16, 1975 the house was officially opened to the public, and today the AHC continues to own and maintain the mansion as a historic house museum.

Modern Impact

The Kirvens and McLeods were successful in preserving intact many of the mansion’s outstanding architectural features. Unfortunately, time and progress took their toll on the porter’s lodge, summerhouse, outbuildings, artificial lake, and the Gaineswood plantation itself.

The artesian well for the lake stopped overflowing in 1901, and the lake dried up shortly afterward. In the 1940s, the city of Demopolis condemned and filled in the lake, upon which was constructed Demopolis High School (now Demopolis Middle School) in the 1940s.

As mentioned previously, the estate that was Gaineswood Plantation increased in size from the original 480 acres to about 1600 acres by 1860. However, since 1900 the size of the estate has dwindled significantly to the 4.5 acres now owned by the AHC.

U.S. Highway 80 bisects on an east-west axis what was once the heart of Gaineswood plantation. Accompanying retail, industrial, and residential growth have succeeded in eliminating almost entirely any visual or physical features indicating the prior existence of a cotton plantation.

A notable exception is the most imposing surviving remnant of Gaineswood Plantation---the mile-long Whitfield Canal.

Built 1845-1863 by slaves under the direction of Nathan Bryan Whitfield, the Canal was successfully engineered to keep Whitfield’s cropland from flooding by diverting overflow surface water westward toward the Tombigbee River. In some places the Canal is 30 feet deep. Located south and east of Gaineswood, the Canal extends to within about 1/8 mile southwest of the mansion.

Canal near Cedar Avenue south of Gaineswood

Still intact today, the Canal continues to serve a crucial drainage function, protecting adjacent businesses and residences from flooding.

A State of Alabama historical marker is located near the Canal at E. Morgan and Walnut St. The canal can also be seen from Cedar Avenue, a wooden footbridge south of N. Main St., and other locations throughout town.

Selected Bibliography

Galloway, Regina Ulmer. Gaineswood And The Whitfields Of Demopolis. Skinner Printing Company, Montgomery, 1994. For Nellie Whitfield Ulmer.

Gamble, Robert. The Alabama Catalog: Historic American Buildings Survey: A Guide To The Early Architecture Of The State. The University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, 1987.

Kennedy, Roger G. Greek Revival America. Stewart, Tabori, & Chang, Inc., 1989. ISBN 1-55670-094-6.

Pate, James P. The Reminiscences of George Strother Gaines: Pioneer and Statesman of Early Alabama and Mississippi, 1805-1843. Edited with an Introduction and Notes by James P. Pate. The University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, 1998. (Originally published in The Alabama Historical Quarterly, Vol. 26, Nos. 3 and 4, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, 1964)

Patton, Walter S. General Nathan Bryan Whitfield And Gaineswood. Alabama Historical Commission, Montgomery,1972.

Smith, Winston. Days Of Exile. W.B. Drake And Son, Printers, Tuscaloosa.1967.

Tharin, W.C. A Directory of Marengo County, For 1860-61. Mobile, 1861. Reproduced By The Marengo County Historical Society, 1973.

Wilson, Eugene M. A Guide To Rural Houses Of Alabama. Alabama Historical Commission, Montgomery, 1975.